“Nothing stands up more free from blame in this world than a pine tree.”

Who else could have written those words than Henri David Thoreau. Thoreau is one of history’s most gifted naturalists and writers. And he was, very likely, one of the truest friends that a tree would ever have.

We know well of Thoreau’s love for nature as he shared his passion with readers in Walden and other writings. He was a careful observer of nature: from the depth of Walden Pond to the daily activity of ants. But perhaps his greatest passion was for trees.

The trees, he wrote, knew things that he did not and would never know. He looked at trees every day. He studied their shape, color, texture. He measured them. He interpreted their expressions and their traits. He glorified them in writing and in sketches. To Thoreau, trees were family, friends, allies, even more. In his journal on December 1, 1856, he wrote, “There was a match found for me at last. I fell in love with a shrub oak.”

Thoreau felt a personal connection to trees that helped him “see” them in ways nearly all people never will. He admired the oak because it was strong, sturdy and resistant. He identified with the pine because he saw it as rebellious. He was so attached to one large Elm tree that was cut down, he wrote a 3,000-word obituary for it.

Thoreau adored the way trees changed in all seasons. He appreciated the ability of trees to survive all four New England seasons with vitality. But the trees of winter were the most fascinating to him.

Rather than keep him indoors, the cold and snowy New England winters offered him a new way to observe trees. Winter made the world “new” for him. “How new all things seem. It is like the beginning of the world,” he wrote.

The winter season made it easier to see the leafless limbs of trees, especially against a backdrop of white snow. “The trees, especially the young oak covered with leaves, stand out distinctly in this bright light from contrast with the snow,” he wrote. Thoreau loved seeing bare trees now draped in snow or sheathed in ice.

Seeing trees as Thoreau did reveals a new world hidden in plain sight. It is a gift that we can give to ourselves, and to our children. Feeling a connection to an individual tree, or to a species of tree, or a forest, will connect us to the natural world in ways we couldn’t imagine before.

Thoreau was a dedicated naturalist. But you and your children do not have to live in a cabin alone in the woods to develop a gratification for trees. You and your young naturalists can develop a lifelong appreciation for trees by adopting some of these habits we can borrow from Thoreau.

How to Be Love Trees Like Thoreau:

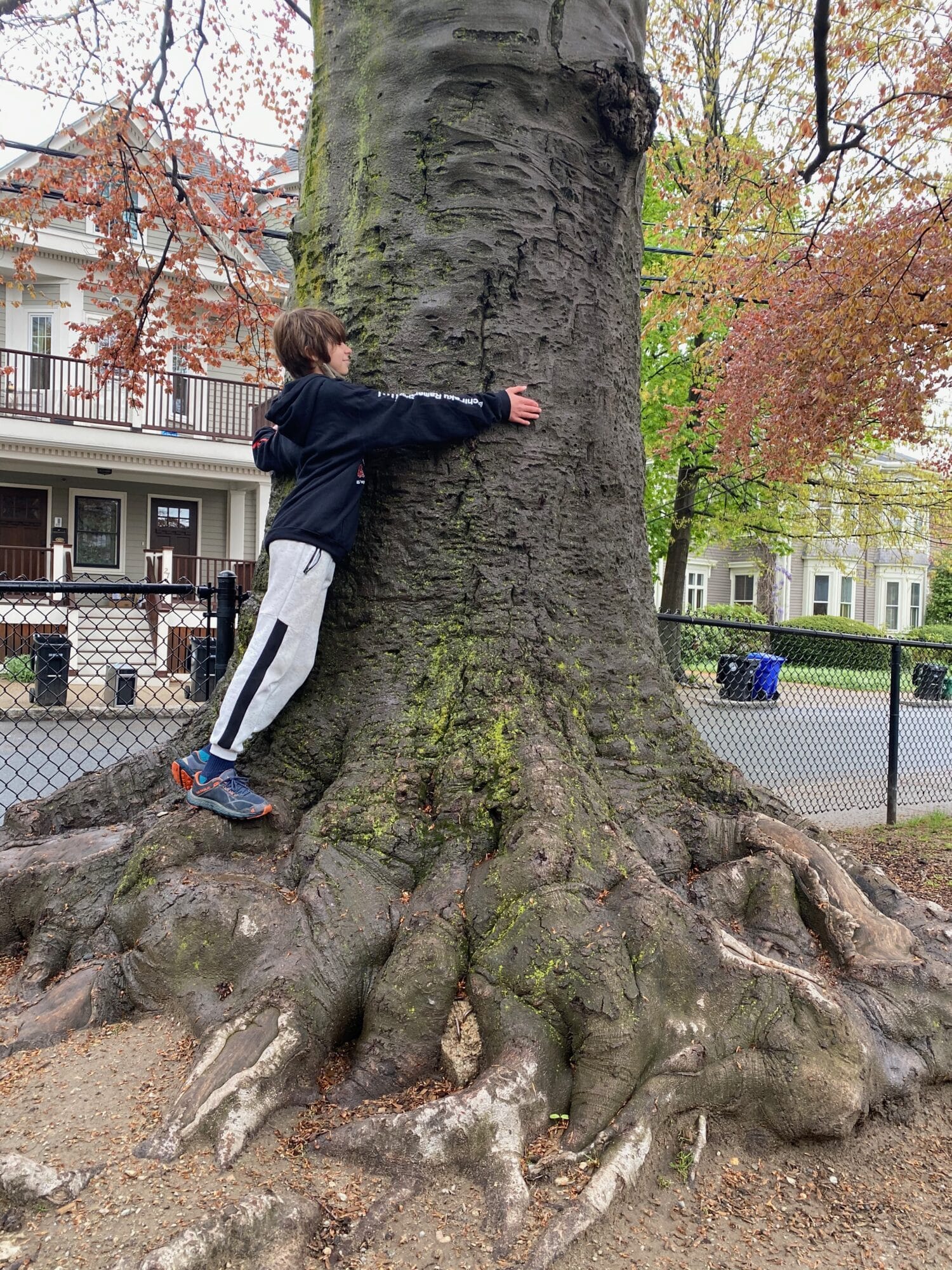

- Know your local trees. Thoreau knew individual trees all over Concord. He visited them in all seasons and times of day. A great way for your child to get to know local trees is to become a tree friend to one, visiting it and observing it through all seasons.

- Take your time. Thoreau could never get sick of looking at trees. In his journal he wrote, “I could study a single piece of bark for hours.” There are so many intricate parts to one tree. Help your child appreciate the fascinating parts that make up the whole by taking time to notice what makes each piece unique.

- Overlook nothing. No part of the natural world was overlooked and underappreciated by Thoreau. He appreciated all parts of the tree: the root, trunk, bark, branch, crown, leaf, blossom, and cone. Rotting logs and dead leaves fascinated him. “Pitch pine cones very beautiful, not only the fresh leather-colored ones but especially the dead gray ones.” He inspected lichens for hours on rainy days.

- Use all of your senses. Thoreau used all of his senses. He snapped twigs to sniff their bark. Listened to the moan and creak of hardwoods in the winter and to the roar of wind in the woods. Nibbled lichens and moss.

- Write about them but choose your words well. Thoreau chose his words carefully when writing about trees. He never felt like he got his description of nature right. He wrote, rewrote, and questioned his words. And certainly use a nature journal to capture feelings and observations.

Further Reading: Thoreau and the Language of Trees, Richard Higgins