As new generations reach for words to describe the world around them they often delve into the vocabulary of nature. Words such as stream, tweet and cloud have been adopted and given new meaning, in these cases to describe elements of the technological world in which we now live. But is this at the expense of the natural world?

A 2019 survey of 1000 children would suggest so. It showed that 83% of those questioned could not identify a bumblebee and nearly half could not identify brambles, blackberries and bluebells. Surveys like this support the idea that British people are losing touch with nature.

There has been research into how languages and words evolve and become extinct and even how others survive. But there is a lack of academic research which looks specifically at the language of nature.

But a collaborative project from King’s College London, the Leverhulme Trust and Lancaster University is underscoring the very real relationship between people’s attitudes to nature and the language we use. Initial findings from that project show that red squirrels were represented in the 19th century as being pests in need of culling.

They were not described as “cute” or shown in visually appealing ways. The arrival of the grey squirrel in 1876 changed public attitudes as red squirrel numbers declined and the language of the media clearly changed over time towards the modern, positive image.

Read more: When languages die, we lose a part of who we are

As children – and even as adults – we can only identify and talk about what we have learned or been taught. For example, Guardian columnist and naturalist George Monbiot has argued that each generation is normalising the erosion of the environment. Children, he says, are growing up with a new and depleted baseline of what they see as the “normal” range of wildlife around them. Similarly, I believe, that each generation grows up with a new and depleted baseline of how we talk about nature and wildlife.

So a new GCSE in natural history can only be a good thing if it helps teenagers reconnect with wildlife by learning the names and characteristics of plants and animals. The new qualification is the brainchild of writer Mary Colwell and has been supported by Green party MP Caroline Lucas and by senior figures at the University of Cambridge.

I have researched language and language use for 21 years but I became more keenly aware of the relationship between noticing the natural world and being able to name bits of it when I read Robert MacFarlane’s book Landmarks. MacFarlane points out forgotten words such as “ammil” (a Devon word for a fine film of ice that covers leaves and twigs) and a “smeuse” (a gap in a hedge made by the passage of a small animal). I have noticed a lot more ammil and smeuses since I read the book, which describes hundreds of words from across the British isles for snow, ice, animal calls and noises.

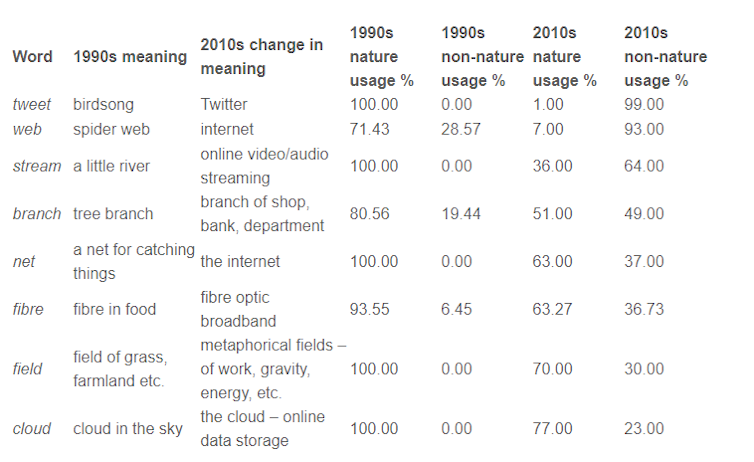

Despite this abundance, the public’s vocabulary is being whittled down when it comes to nature, as a National Trust project found. The research discovered that words from the 1990s which were entirely used to refer to the natural world, have now taken on meaning from the world of computers and the internet. Cloud, stream and tweet are such examples. In a comparable dataset from the 2010s the National Trust study shows that cloud has fallen to 77%, stream is down to 36% and tweet is down to 1% of its old usage in everyday conversation.

The trust’s regional director for the midlands, Andy Beer, said: “As a nation we are losing our connection with nature… If today’s children aren’t connected to nature, then who is going to stand up for our countryside and wildlife in the future?”

Changing attitudes to nature

So does this apparent change in language use reflect changing attitudes to the natural world? A study by Natural England suggests it does, with evidence that children in London and the West Midlands are the least likely to spend time outdoors in woodlands or other similar wild places.

Meanwhile, another study from 2018 found that different ethnic groups can have different ideas when it comes to what comprises nature. In the study, all ethnic groups listed trees, forests and plants as terms they associate with nature.

But there was more variance when it came to animals. Around 40% of “other” ethnicities said they thought of animals when asked about “nature”, along with 28% of white people. This dropped to just 14% when the question was asked of black people. This is an important reminder that this must not be a discussion restricted to white, middle-class academics. There needs to be participation from across society to fully understand what could be causing a decline of nature words.

Read more: Fight on to preserve Elfdalian, Sweden's lost forest language

Of course, language is always changing and evolving. Children will not stop playing computer games and they will not stop having an interest in new technology – and nor should they. But the adults in this conversation must explore ways to combine modern technology with a love of nature.

People already take their phones and tablets on citizen science trips to study butterflies and bugs. So let’s welcome the new technology, create apps and develop innovative ways for children to learn words from both worlds. Wouldn’t it be great to see young people tweeting about ammil covered leaves and smeuses as they take their first steps into the great outdoors?![]()

Glenn Hadikin, Senior Lecturer of English Language and Linguistics, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.